You’re standing in a bookshop, holding two copies of the same novel. Each bears a different translator’s name on the cover, and each offers a distinct way of hearing the same book. Which one should you choose?

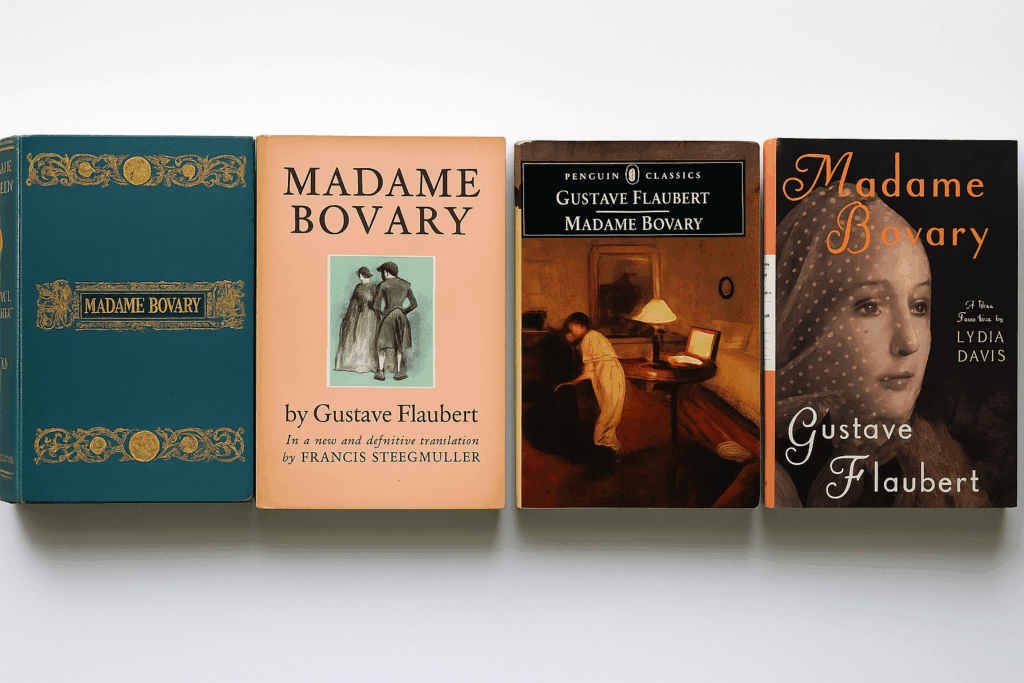

For many readers of world literature, this small dilemma arises more often than expected. Classic works such as The Odyssey, Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary have been translated into English many times, sometimes only a few years apart. Yet when we browse the shelves, few of us know how to tell these versions apart.

This article explores what drives the creation of new translations and how readers can decide which version best suits their taste or purpose. It considers the patterns that shape every translation, from a translator’s style and historical context to how a version feels in your hands as English prose.

Why Multiple Translations Exist

When a literary work is translated more than once, it reflects more than simple repetition. Each version arises from a fresh encounter between languages and times, shaped by new readers, styles, and cultural expectations. Retranslation is not about replacing what came before but about hearing the work again, in a voice that speaks to the present.

When Language and Time Reshape the Text

Every translation is a product of its moment. Languages change, readers change, and so do our ideas about what good prose should sound like. In her foundational book Translation Studies, first published in 1980, the scholar Susan Bassnett explains this phenomenon. She argues that because our own language and literary norms constantly evolve, a translation made for one generation will inevitably seem dated to the next, creating a continual need for new versions.

That sense of linguistic ageing is one reason publishers commission fresh versions of well-known works: to let readers hear the text in a voice that suits their own era. As Cathy McAteer notes in Translating Great Russian Literature, the Penguin Classics series was founded on a clear principle from its first editor, E. V. Rieu. He believed a translation should recreate the original’s impact, making a modern reader feel the same sense of excitement or drama as the book’s earliest audience.

When Translators Hear the Work Differently

If some retranslations arise because languages evolve, others emerge from disagreement. Translators may find that earlier versions misrepresent tone, omit nuances, or distort meaning. When Lydia Davis took on Madame Bovary for Penguin Classics in 2010, she explained in an interview with The Paris Review that she avoided reading earlier English versions so she could form “her own understanding” of Flaubert’s text.

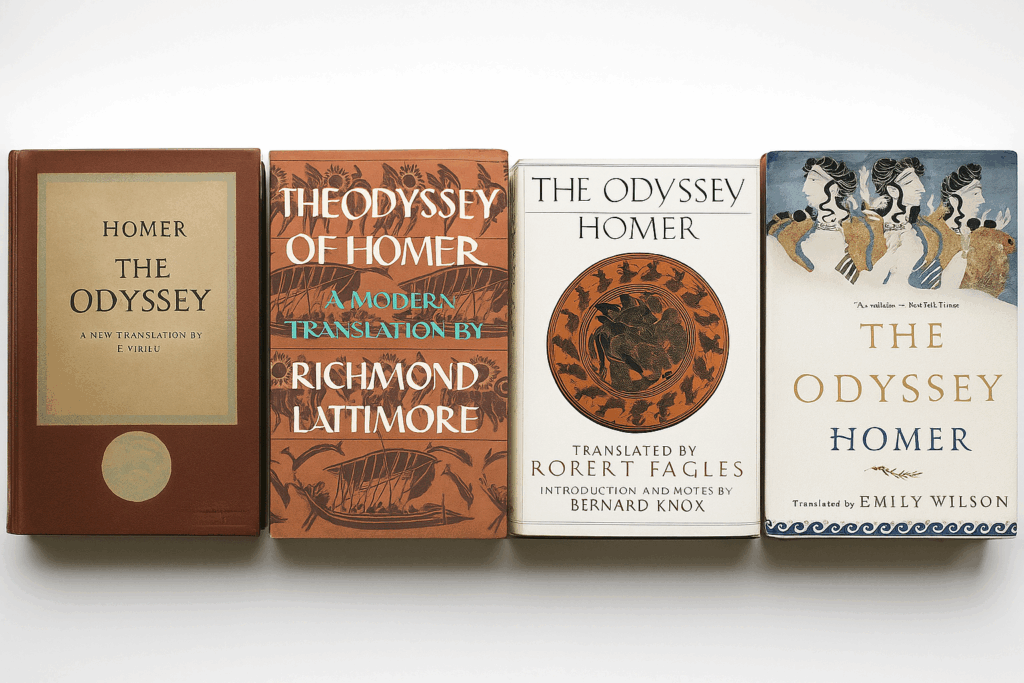

Publishers, too, often present new translations as renewals, ways of re-hearing a classic for a new generation. When The Odyssey appeared in Emily Wilson’s English verse, published by W. W. Norton in 2017, it was introduced as “a vivid new translation … [that] recaptures Homer’s nimble gallop and brings an ancient epic to new life.” The phrasing itself implies a corrective impulse: not simply repeating the past, but reviving it in a form attuned to contemporary readers.

E. V. Rieu (Penguin Classics, 1946); Richmond Lattimore (Harper & Row, 1965); Robert Fagles (Viking Books, 1996); Emily Wilson (W. W. Norton, 2017).

When Faithfulness Takes New Forms

Faithfulness, too, is never a fixed measure. What readers in one era consider “true to the original” often reflects the values and idioms of their own time. Penguin’s retranslations of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky were promoted as being closer to Russian syntax and humour, resisting the smoother English phrasing that had dominated earlier versions. Such claims of fidelity reveal how cultural expectations of clarity, elegance, or foreignness influence what counts as an authentic rendering.

When Scholarship Reveals What Was Lost

Beyond language and fashion, there are scholarly reasons for retranslation as well. New versions are needed when academics establish a more accurate source text, or when censored passages are finally restored. Early English versions of Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, for instance, were based on an incomplete manuscript. A re-evaluation of cultural context can also demand a new approach. This reflects what Bassnett and André Lefevere later called the “cultural turn” in translation studies, the moment when each generation re-examines classic works through new critical eyes.

This means that different translators can approach the same author with distinct artistic goals. The first English One Hundred Years of Solitude, translated by Gregory Rabassa in 1970, perfectly captured the propulsive energy of the Latin American Boom, while Edith Grossman’s Love in the Time of Cholera (1988) sought a denser musicality closer to the original Spanish. Both translations are masterpieces; neither cancels the other.

When Publishers Return to the Classics

Practical motives play a role too. When rights to older translations expire, publishers can lose their exclusive hold on a classic. Commissioning a new version creates a fresh, copyrighted edition. This commercial cycle aligns with the editorial vision of figures such as Edwin Frank of NYRB Classics, who treats the canon as a living body of work that needs constant renewal for new generations. Translators themselves sometimes return to beloved works out of artistic curiosity, wanting to re-hear the text in their own voice, as Edith Grossman described in her lifelong engagement with Cervantes.

So when readers find several versions of the same book on a shelf, what they are seeing is not duplication but dialogue, a conversation between times, languages and interpretations. Each new translation extends that conversation, keeping the work alive in English.

How to Choose the Best Translation

Standing before several versions of the same book, a reader may wonder how to tell which translation will offer the most rewarding experience. There is no single rule to follow, only patterns that emerge from the way translators, scholars and readers talk about their work. What we can do, however, is learn to recognise those patterns: the signs that tell us what kind of translation we are about to read, and whether it matches what we are looking for.

Listen for the Translator’s Voice

The first and perhaps most revealing clue is voice. Edith Grossman reminds us in Why Translation Matters (2010) that what we read in translation is the translator’s writing. Each translator brings their own rhythm, diction and emotional range, which can subtly reshape the author’s tone. Reading a few pages aloud often reveals whether the prose feels alive or laboured, whether it carries the author’s cadence or substitutes another. Lydia Davis’s Madame Bovary is crisp, restrained and almost ascetic, while Geoffrey Wall’s version flows with warmth and lyricism. Both are recognisably Flaubert, but each draws the reader into a different texture of English.

Compare Translation Styles and Approaches

Next comes the question of approach, how closely a translator stays to the source and what kind of English they aim to produce. Umberto Eco described translation as a process of negotiation, where the goal is to achieve an equivalence of sense for sense, not word for word. Some translators prefer to domesticate the text, making it sound comfortably English; others preserve its foreignness, leaving a trace of strangeness in word order or idiom. Lawrence Venuti famously argued that the more fluent a translation, the more invisible the translator. For readers, this means fluency is not the same as quality: a perfectly smooth version may have erased too much of the original’s texture.

Notice How Translators Balance Fidelity and Freedom

A third dimension is fidelity, the question of how closely a translation follows its source in meaning and tone. Some versions stay near the original syntax, others interpret more freely to capture spirit rather than structure. Davis undertook her Madame Bovary after finding earlier English versions inaccurate or loosely paraphrased, while Wilson’s Odyssey aimed to strip away moralising or gendered distortions from Victorian editions. Such differences show how translators balance literal accuracy with expressive truth. For most readers it isn’t possible to judge fidelity in a strict linguistic sense without knowing the original language, but you can still sense when a translation feels deliberate, coherent and true to itself.

Read the Preface or Afterword

Context also matters. Translators often explain their aims in a preface or afterword, and these paratexts are invaluable. In her introduction to The Odyssey, Wilson outlines her decision to use a quick, contemporary metre to restore the poem’s speed, clarity and sense of action. Pevear and Volokhonsky, in contrast, justify their literal syntax in Dostoevsky as a way of keeping the Russian alive inside English, an idea Venuti calls “foreignising”. Such notes and prefaces help readers grasp not only what has been translated but how and why.

Consider the Era Behind Each Translation

Another factor is era and register. Bassnett notes in the 2014 edition of Translation Studies that translations date more quickly than originals, as language norms shift with time. Earlier translations may use the idioms and moral assumptions of their period, while new ones mirror the cadence of modern English. This explains why the dignified rhythms of Richmond Lattimore’s Iliad (1951) feel different from Robert Fagles’s (1990) or Caroline Alexander’s (2015): each speaks to its own generation’s ear.

Check Who Published the Translation

Readers should also consider the quality of the edition and publisher. Reputable series such as Penguin Classics, Oxford World’s Classics and NYRB Classics usually commission translations with rigorous editing and scholarly apparatus. The work of an editor like Edwin Frank at NYRB Classics exemplifies this approach. He actively replaces poor or dated translations with stronger ones and commissions introductions from respected modern writers. This level of curation is a clear sign of a publisher’s commitment to quality. A well-edited volume with notes, introductions and references often signals reliability and care.

Look for the Cultural Lens

Beyond such technical features, there is the cultural or ideological lens through which a translation is made. Every generation reads differently, and translators bring their moment’s values to the text. Feminist, postcolonial or decolonial readings often revisit works that earlier translators softened or moralised. Venuti’s theory of “visibility” helps explain this: a translator’s decision to make their presence felt can restore balance to voices once suppressed.

See What Readers and Critics Say

A further guide lies in a translation’s reception. Public discussions, from critical reviews in major publications to threads in online reading groups, reveal how a version is experienced in the real world. While professional critics analyse a translator’s stylistic choices, reader communities offer valuable clues about everyday readability and emotional impact.

Academic endorsement provides another strong signal. The editions that consistently appear on university course lists have often passed a rigorous test of scholarly value and endurance. Though popularity alone is no guarantee of excellence, as the most downloaded version is often a free but archaic public-domain text, this collective experience from critics, readers and scholars offers invaluable clues about a translation’s quality and resonance.

Trust Your Ear

Finally, the most important factor is your own purpose. A student may value literal precision and commentary; a casual reader may prefer elegance and flow; a stylistic reader may seek the translator’s distinctive artistry. As David Bellos argues in Is That a Fish in Your Ear? (2011), there can be no single, definitive translation of a work. Every translation, he writes, is a new performance of the original text, unique to the translator and their moment in time. The best way to choose is to open a few versions and see which one you want to keep reading. Trust your ear.