Jerome’s life was as restless as his pen. Born in the Balkans in the fourth century, he travelled widely and studied in Rome. He often clashed with church leaders over doctrine.

It was in Bethlehem, far from the centres of power, that he produced the work that made him the patron saint of translators: the Vulgate, a Latin version of the Bible. He worked slowly, sometimes obsessively, comparing words across languages and searching for precision and clarity.

His choices shaped the rhythm of Latin Christianity for a thousand years. Still, like many translators after him, Jerome’s fame never matched the influence of the text itself. He became a figure both revered and debated. Scholars admired his scholarship, critics accused him of distorting meanings, and readers often forgot that behind the text stood a human mediator.

Jerome’s Translation Philosophy and Lasting Image

Jerome was not an easy man. His letters bristle with quarrels, and his temper earned him enemies as quickly as admirers. Yet his stubbornness shaped his greatest work.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, he refused to rely only on Greek sources for the Bible. He turned instead to Hebrew, a choice that drew suspicion but gave his translation a lasting authority.

In Bethlehem he lived almost as an exile, surrounded by scrolls and dictionaries of his own making. His essays reveal a translator who thought carefully about his craft. He argued that words should be carried across languages for their meaning rather than copied slavishly word by word.

It was a principle that made his Latin version both readable and enduring. Later centuries remembered him in paintings: an old man in red robes, a skull on his desk, his study lit by a thin candle. He became the image of the translator, solitary, meticulous, and at times half-forgotten.

The International Federation of Translators and 30 September

Centuries later, translators would return to Jerome’s story to claim it as their own. His feast day, long observed in the church calendar, offered a symbolic anchor: a reminder of the translator’s essential role and the ease with which that role can be forgotten.

In 1953, in the aftermath of a world war that had made communication across languages a matter of survival, the International Federation of Translators was founded in Paris. Its French title, Fédération Internationale des Traducteurs, gave rise to the abbreviation FIT that is still used today. At its heart was Pierre-François Caillé, a French translator who worked across literature and informational texts. He believed that translators, long scattered and solitary, needed an international body that would give them both solidarity and a voice.

The new federation quickly became a meeting place. Translators who usually worked in isolation could share their concerns, compare working conditions and debate the ethics of their profession. It was also a space where they pressed governments, publishers and international organisations to recognise that translation was not a pastime but skilled and essential work.

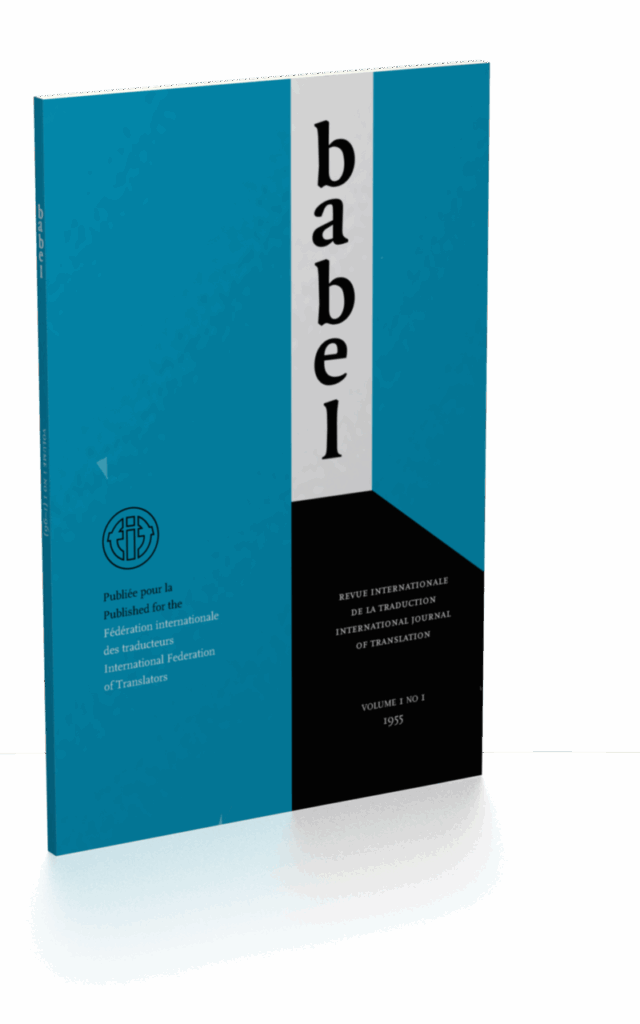

Among those who later shaped FIT was the Croatian literary translator Zlatko Gorjan, known for carrying Moby-Dick and Ulysses into his language. In 1963 he rose to become president of the federation, proof that those who wrestled with sentences on the page could also lead an international community. Gorjan later served on the editorial board of Babel, FIT’s journal founded with UNESCO’s support, where translators began to publish essays and debates in their own names rather than working unseen behind the texts of others.

In 1991, the federation made its connection with Jerome official. It declared 30 September, his feast day, as International Translation Day. The choice was deliberate. Jerome had stood at the beginning of a tradition where the translator was both necessary and invisible. By adopting his day, modern translators tied their own struggle for visibility to his enduring image.

International Translation Day at the United Nations

The story of International Translation Day did not end with FIT. For decades the federation and its members marked the day, but it remained largely within the circle of professional translators. What they wanted, however, was recognition at the highest level, a statement that translation was not only a profession but a cornerstone of international life.

That moment came in 2017. At the United Nations, where six official languages shape the daily work of diplomacy, translators and interpreters had long been the invisible backbone. Every speech, every negotiation and every resolution relied on their voices. Yet their contribution was rarely acknowledged outside the meeting rooms.

It was Belarus that put forward the resolution to the General Assembly, backed by many other member states. The proposal was simple: that 30 September, already marked by translators themselves, be recognised officially as International Translation Day. On 24 May 2017 the resolution was adopted unanimously. For the first time in history, the work of translators was inscribed into the UN calendar of international observances.

The decision was more than symbolic. It tied the solitary labour of Jerome in Bethlehem to the collective effort of modern translators and to the global stage where nations meet. The day became a thread linking past and present, reminding the world that without translators dialogue between cultures, religions and governments would fall silent.

Why International Translation Day Matters Today

International Translation Day is now marked each year with conferences, campaigns and small celebrations. Yet the heart of the day is not in ceremonies but in recognition. Translators are the ones who make books travel beyond their language of birth, who allow leaders to speak across borders, and who let films and poems find new audiences.

Their work is still shaped by the paradox that defined Jerome’s life. Translation is essential, yet translators themselves are often overlooked. In publishing their names may be absent from covers. In diplomacy their voices are heard but not remembered. In the digital age they are sometimes replaced by machines that imitate their labour while ignoring its craft.

The day therefore remains both a celebration and a reminder. It honours the solitary scholar in Bethlehem, the professionals who built an international federation in Paris, and the interpreters who give life to debates at the United Nations. It also points to the continuing need to see translators not as shadows behind the text, but as authors of understanding between cultures.