Ivan Klíma died in Prague on 4 October 2025, aged ninety-four. The obituaries and reports that followed in The Guardian, Radio Prague International, and The New York Times were respectful and restrained, fitting for a writer whose work had always spoken with modest conviction. They recalled a life that moved through many kinds of silence: a childhood spent in the Terezín ghetto, the years of censorship after 1968, and the long season of writing that followed. Yet for many readers, Klíma’s story began elsewhere, not in biography, but in translation.

It was through translation that his voice travelled first, often while it was still forbidden at home. English-language readers encountered him through translators who treated literature not as ornament but as an act of care. In an interview with The Independent, Paul Wilson, who rendered My Golden Trades and other works into English, spoke of the quiet labour of carrying modern Czech writers across borders. Another of his translators, Ewald Osers, introduced Love and Garbage to Western readers in 1990, when Czech voices were only beginning to cross the Iron Curtain openly. And when Radio Prague International marked Klíma’s eighty-fifth birthday in 2016, it chose a single word for what his writing and its translations seemed to transmit: empathy.

In that afterlife of a voice, the translator becomes less an interpreter than a custodian. What remains, after the news cycle moves on, are the books that keep speaking in many languages, each one a door left open.

A writer whose language travelled

Klíma’s path to foreign readers was shaped as much by silence as by speech. After the Soviet invasion of 1968, he was expelled from the Union of Writers and banned from publishing in Czechoslovakia. For nearly two decades, his books circulated in samizdat, typewritten copies passed quietly from hand to hand, or appeared with exile publishers abroad before reaching readers through translation. What censorship tried to contain, translation released.

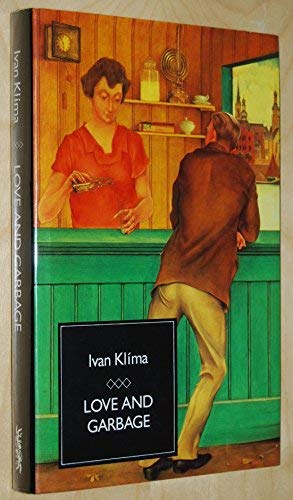

Klíma’s work first appeared in English in the mid-1980s, when a collection of his short stories was translated and published in London. The major wave of translations, however, came in the early 1990s with Love and Garbage, Judge on Trial, and My Golden Trades, which together brought his fiction to a much wider international readership.

In his memoir My Crazy Century, published in English by Grove Press in 2013, Klíma reflected on what it meant to see his own words return to him in another language, at once distant and faithful, a proof that the stories had survived. For readers outside Prague, those translated books were not simply literature from behind the Iron Curtain; they were glimpses of a shared moral landscape, spoken in an adopted tongue.

Translators as caretakers of Ivan Klíma’s voice

Ivan Klíma’s English voice was shaped, line by line, by several translators whose own lives crossed borders. His first work to appear in English was the short-story collection My First Loves, translated by George Theiner and published in London in 1986. A few years later, Ewald Osers and A. G. Brain brought his major novels into English at the turn of the decade, while Paul Wilson would carry his voice to new readers in the 1990s and beyond.

Ewald Osers, born in Prague in 1917, fled to Britain before the Second World War and became one of the most prolific mediators of Central European literature. By the time he translated Love and Garbage in 1990, he had already brought the poetry of Miroslav Holub and the plays of Václav Havel into English. His rendering of Klíma’s prose, plain, rhythmic, and edged with irony, reflected both a shared linguistic ancestry and a lifetime spent translating loss.

A generation younger, Paul Wilson arrived in Prague from Canada in the 1960s to teach English and stayed long enough to be expelled by the communist authorities in 1977. Translating Klíma later became, he has said in interviews, a way of keeping Czech culture alive while it was being suppressed. He described translation as a kind of stewardship, carrying voices that could not yet travel on their own.

Neither Osers nor Wilson treated Klíma’s work as testimony alone. What drew them was the quiet moral tension beneath his stories: the struggle between decency and compromise, love and resignation. Their English versions preserved that stillness without softening it. Through them, Klíma’s moral universe, ordinary men and women facing impossible choices, found a language that sounded both foreign and familiar.

The life of his works abroad

Once his books began to appear in English, they travelled quickly. Publishers such as Chatto & Windus and Granta Books, both later linked with Penguin’s wider publishing network, positioned Klíma beside other Central European writers who had crossed from censorship into international readership. On book jackets, he was often introduced as “a moral voice of Czechoslovakia” or “the conscience of Prague.” The phrasing was sincere, yet it framed his fiction within a familiar Cold War narrative, the dissident writer as moral witness.

In reviews, English-language critics responded less to ideology than to tone. The New York Times praised Love and Garbage for its “precise, unsentimental compassion,” while The Guardian noted the “wry humanism” that survived translation. Through these responses, a public image emerged: Klíma as the chronicler of decency under pressure, a voice of endurance rather than protest.

Over the following decades, new editions quietly kept him in circulation. My Golden Trades and Love and Garbage remain available through Granta’s backlist; excerpts of A Childhood in Terezín, translated by Paul Wilson for Granta magazine, are still read in classrooms. For readers discovering him now, often after the news of his death, these English translations are not relics but renewals, the form in which his work continues to breathe.

First UK English edition, Granta Books / Penguin Books Ltd, London, 1992.

The translated voice as legacy

For a writer who spent much of his life silenced, Ivan Klíma continues to speak in languages not his own. His death in Prague closed one circle, but the others, those drawn through translation, remain open. The English editions that once carried his stories across the Iron Curtain now travel through new circuits of reading: digital reprints, classroom anthologies, libraries in cities he never saw.

In My Crazy Century, Klíma reflected that truth loses its power only when we are silent. His translators ensured he was never entirely so. Through them, the moral clarity of his fiction, neither resigned nor triumphant, reached readers who shared none of his circumstances yet recognised the quiet endurance of his characters.

Today, when most of his original Czech works are accessible again, it is still through translation that his voice is most widely heard. The act that once preserved his existence has become the form of his survival. Literature, he often suggested, begins with listening; translation, too, listens, and in listening, it keeps a life alive.