When the Swedish Academy announced that László Krasznahorkai had been awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature, it felt like the culmination of a long, labyrinthine sentence finally reaching its full stop. Known for his sprawling syntax and apocalyptic vision, the Hungarian novelist has been called “the contemporary master of the apocalypse” and “Kafka’s legitimate heir.” His novels – Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, Seiobo There Below and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming – create a world of endless motion and moral gravity, where despair and transcendence coexist in the same breath.

Yet few of the readers now celebrating László Krasznahorkai’s Nobel have ever encountered him in Hungarian. His global reputation was built through the work of his translators: George Szirtes, Ottilie Mulzet and John Batki, whose English renderings carried his famously untranslatable prose across linguistic borders. Without them, the dense music of his sentences, the meditative slowness of his thought and the eerie humour that pulses beneath his despair might never have reached the Anglophone world.

As headlines hail László Krasznahorkai’s triumph, this piece turns to the invisible voices behind his – the translators who shaped how English readers imagine one of the world’s most enigmatic living writers.

George Szirtes: The First Bridge

Long before the Nobel, there was a single English voice attempting to contain László Krasznahorkai’s endless sentences. That voice belonged to George Szirtes, the Hungarian-born poet who translated Satantango in 2012. Szirtes left Hungary as a child after the 1956 uprising and grew up in England, later relearning his mother tongue as an adult. That distance, both linguistic and emotional, made him the perfect intermediary between two languages that rarely meet.

In his 2015 Guardian essay, László Krasznahorkai described Szirtes’s translation as an act of extraordinary endurance, writing that reading him “feels like being caught in a slow hurricane.” Szirtes’s task was to preserve that storm in English, to let the language hold its breath without breaking. His translation of Satantango won the Best Translated Book Award in 2013, but its true success lay in something quieter: it made readers feel the pull of a voice that resists translation.

Ottilie Mulzet: The Interpreter of the Untranslatable

If Szirtes opened the door, Ottilie Mulzet furnished the interior. The Canadian-born, Prague-based translator has rendered some of László Krasznahorkai’s most complex works into English, including Seiobo There Below, Destruction and Sorrow Beneath the Heavens and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming, which won the National Book Award for Translated Literature in 2019.

In an interview with The Paris Review, Mulzet reflected that “each language shapes reality differently”, explaining that her goal was not to make Hungarian sound English but to let English bend around Hungarian thought. Her English is patient and lyrical, mirroring the mystical pulse of the original. Through her translations, English readers encountered not just a novelist but a metaphysical thinker – a writer who transforms syntax into prayer.

John Batki: The Quiet Collaborator

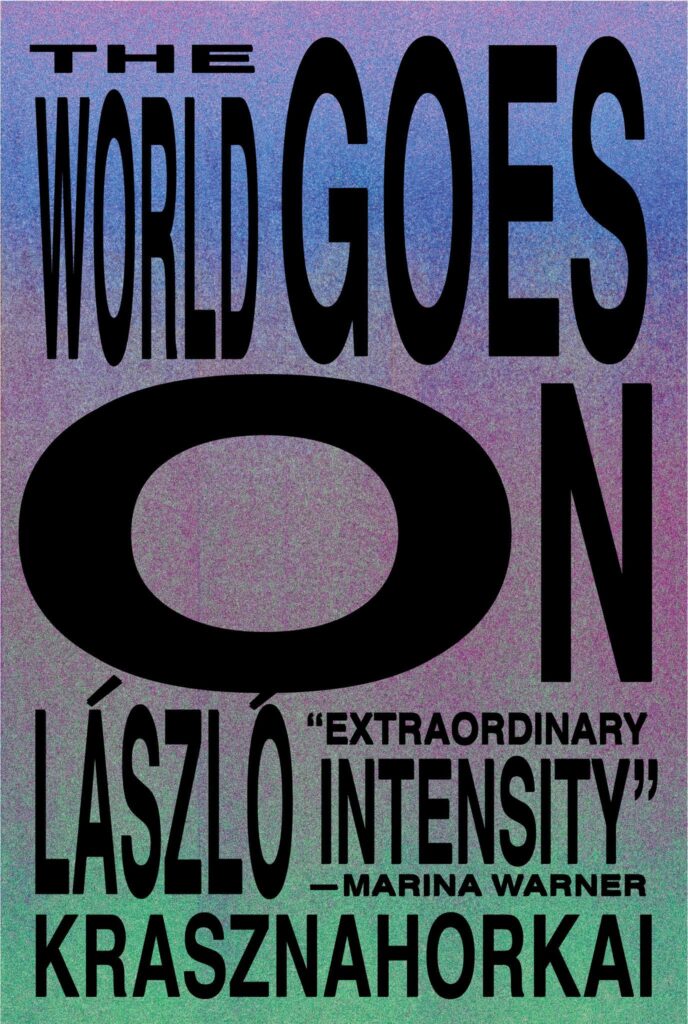

Less visible than his peers but no less essential, John Batki has contributed to several of László Krasznahorkai’s English editions, including The World Goes On and Spadework for a Palace. His work often overlaps with that of Szirtes and Mulzet, showing how translation, in this case, becomes a collective art. In The World Goes On, all three translators worked side by side, each shaping a piece of the whole – an unusual but fitting arrangement for a writer whose sentences themselves seem to resist boundaries.

Batki has described translation as “listening for the music under the words”, a phrase he has used in interviews discussing his work with László Krasznahorkai and other Hungarian authors. His precision and restraint help balance the wild music of Krasznahorkai’s thought. His role is quieter, but it reflects something essential about translation: that it is not a solitary act but a conversation across voices, styles and generations.

Together, Szirtes, Mulzet and Batki have built the English-language identity of László Krasznahorkai. Their translations, made years apart and across continents, flow into one another with surprising unity. For many readers, the English voice of Krasznahorkai is not the echo of a single translator but the harmony of three. Each brings a distinct cadence – Szirtes urgency, Mulzet stillness, Batki precision – yet together they shape the way the Anglophone world imagines him.

The English László Krasznahorkai and the Nobel Moment

The version of László Krasznahorkai that most of the world knows does not speak Hungarian. It speaks in the rhythm, syntax and daring of English – the one built by Szirtes, Mulzet and Batki. It was through their translations that his work reached major Anglophone publishers, critics and universities. Satantango’s English edition revived interest in a writer who had long been a secret among European readers. Seiobo There Below and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming carried him into the global conversation, winning translation prizes that introduced his name to new audiences.

Without these English versions, László Krasznahorkai might have remained a writer admired by specialists – revered but remote. Instead, his translators made his difficulty legible. They turned his endless sentences into an experience English readers could inhabit, not just observe. Their work did not simplify him; it invited readers to dwell inside his density, to feel how thought can unfold without a full stop. That experience is what ultimately defined his reputation as the “master of the apocalypse” – a reputation that reached the Swedish Academy.

The Nobel Committee may or may not have read László Krasznahorkai in English, but the idea of him that reached them – the myth of the uncompromising visionary, the novelist of spiritual endurance – was shaped by translation. His English voice became the global one, echoed in reviews, academic studies and interviews. Translation did not follow recognition; it created the conditions for it.