Nearly eight decades after his death, Osamu Dazai has become an unlikely figure of fascination for a new generation of readers. Clips about him circulate on TikTok, he appears as a character in the manga and anime Bungo Stray Dogs, and English translations of his work continue to multiply. The Japanese writer, once considered too bleak or eccentric for international audiences, now feels strikingly contemporary. The reasons for this renewed attention are complex, but translation is central.

A Writer in Constant Re-translation

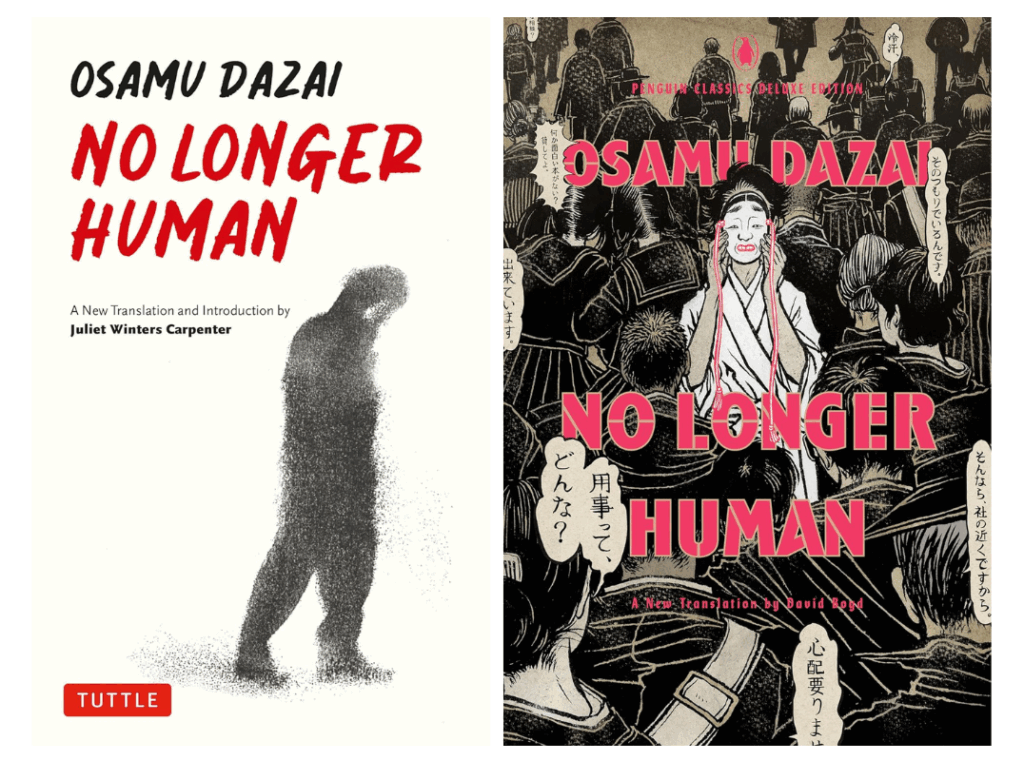

Dazai first reached English readers in the late 1950s when Donald Keene translated his work. Since then, translations have appeared sporadically, often of his most famous novel No Longer Human. The past decade, however, has brought a surge. Sam Bett introduced Flowers of Buffoonery through New Directions in 2023, Juliet Winters Carpenter published new Tuttle editions of No Longer Human in 2024 and The Setting Sun in 2025, and Ralph McCarthy has produced collections such as Self-Portraits and Blue Bamboo. Most recently, bilingual poet Leo Elizabeth Takada has released Retrograde, a trio of early short stories, with One Peace Books in 2025. Looking ahead, David Boyd’s new No Longer Human for Penguin Classics is scheduled for 2027.

Each of these translators highlights a different side of Dazai. Bett stresses his ironic humour, Boyd his directness and vulnerability, while Takada draws out the intimacy of his voice. The result is that Dazai never appears fixed; he is constantly reframed for new readers.

Copyright and the Market

Part of the current wave has a structural explanation. With Dazai’s work now out of copyright, publishers face fewer restrictions and costs. This makes new translations more viable, particularly for smaller presses. Yet copyright alone does not explain his popularity. Other early twentieth-century Japanese authors such as Kenji Miyazawa are also public domain, while others like Edogawa Ranpo are not yet. The fact that Dazai, rather than these peers, has become a global presence suggests that translation choices, publishing strategies, and the sheer resonance of his themes matter as much as legal status.

Why Young Readers Relate

Dazai described the “beauty of weakness” in his essays, and his fiction often circles themes of alienation, despair and self-mockery. No Longer Human, first serialised in 1948, remains a cult text for its depiction of a man unable to fit into society. Yet his appeal is not limited to bleakness. In stories like those collected in Retrograde, readers encounter playful experiments with form, irony and absurdity.

Younger readers often speak of feeling unusually close to Dazai, as though he is confiding in them personally. His narrators rarely claim authority; they stumble, complain, joke and fail. That vulnerability, sharpened through translation, allows a century-old voice to feel uncannily direct.

Humour and Farce in Osamu Dazai’s Work

Critics note that focusing only on despair misses half of Dazai’s power. Much of his writing is humorous, even clownish, in its treatment of human weakness. His characters make fools of themselves, satirise social pretensions, and expose the absurdity of everyday life. Translators such as Bett and Boyd argue that preserving this humour is key to understanding why his work resonates so strongly today.

Osamu Dazai: Myth and Life

Dazai’s life story cannot be separated from his literary afterlife. He attempted suicide several times before finally drowning with his lover in 1948, just as the last instalment of No Longer Human appeared in print. The blurred lines between his art and his fate continue to fascinate readers, much like the myths that surround musicians such as Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse.

But while the myth draws readers in, translation ensures that Dazai’s words, rather than just his biography, are heard. Each new version reintroduces him not as a relic of postwar Japan but as a writer who can still speak to the struggles of today.

An Author Always Renewed

The contradictions that shaped Osamu Dazai, comic and tragic, self-mocking and despairing, are precisely what make him enduring. Translation sustains those contradictions, carrying them across languages and generations.

Love him or hate him, Osamu Dazai remains unmistakably himself. What changes is the voice in which we hear him, a voice that each translator helps to renew.

This piece was inspired by a recent article in The Japan Times by Kris Kosaka on Osamu Dazai’s resurgence, which prompted us to explore how translation continues to shape his global voice. For a deeper reading of that article, you can find it here.