For most of literary history, translators have been invisible. They appear in acknowledgements, if at all, and their labour is often taken for granted. Yet in recent years something unusual has happened: translators have stepped into fiction itself, not only as authors, but also as protagonists.

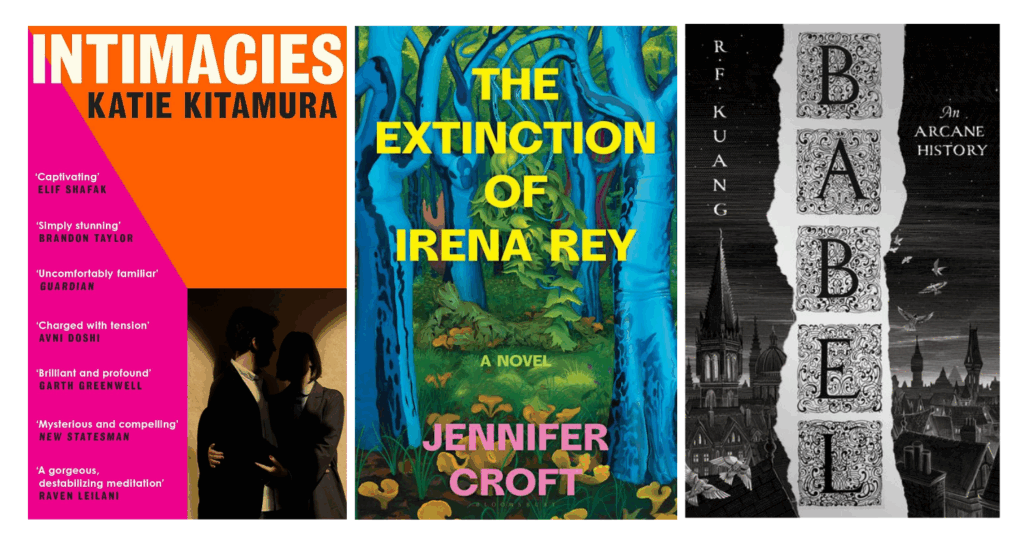

In novels like Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies (2021), Jennifer Croft’s The Extinction of Irena Rey (2024), and R. F. Kuang’s Babel (2022), the central figure is not the usual detective, lover or misfit artist, but a translator. These characters are tasked with carrying meaning across languages, and with that task comes vulnerability, conflict and unexpected power.

Visibility through fiction: translators as main characters

When a translator becomes a character, the work of translation itself is dramatised. Readers are invited to imagine what it feels like to interpret the words of a war criminal (Intimacies), to join a team of literary translators obsessed with their missing author (The Extinction of Irena Rey), or to discover how translation could literally fuel an empire (Babel).

These stories capture something important: translation is not a neutral act. It is entangled with ethics, politics and identity. Fiction makes this visible in a way that non-fiction accounts or translator prefaces rarely can. By turning translators into protagonists, novelists allow readers to glimpse the intense psychological and cultural stakes behind what often seems like quiet, invisible work.

The ambivalence of the translator’s role in novels

Yet these portrayals are not always flattering. Translators in fiction are often depicted as fragile or conflicted. Kitamura’s unnamed interpreter in Intimacies is drawn into unwanted empathy with the war criminal whose words she repeats. Croft’s troupe of translators collapse into rivalry, dependence and even absurdity. Kuang’s students at Babel awaken to the realisation that their linguistic skills are tools of imperial violence.

In each case, translation becomes a metaphor for entanglement, a reminder that to cross languages is also to risk losing a stable sense of self. The translator is never entirely in control. They are affected, sometimes overwhelmed, by the voices they carry.

Fiction and reality

What does this new attention mean for translators outside the pages of novels? On one hand, it is encouraging: translators are no longer invisible. Their work is being recognised as dramatic, worthy of storytelling. On the other hand, there is a gap between the heightened visibility of fictional translators and the continuing invisibility of real ones. Translators of literature still face chronic underpayment, limited recognition and marginalisation in the publishing industry.

Perhaps this is why the figure of the translator resonates so powerfully in fiction. The translator embodies the contradictions of our globalised world: essential, yet overlooked. A bridge across cultures, yet precariously positioned between them.

Why this matters

For readers, these novels offer an opportunity to see translation not as background noise but as a central drama of our time. They remind us that every act of translation involves choices, compromises and risks. And they raise a question worth holding onto: will this fascination with fictional translators also spark greater respect for the real ones who bring the world’s literatures into English?

This article is a free interpretation of Marie Lambert’s essay On Translation Fiction and the Comfort of Monolingualism, published in the Los Angeles Review of Books (September 15, 2025). For a deeper and more meaningful engagement with this theme, I encourage you to read the original article here.